54-Year-Old Woman with Intense Dyspnea and Normal Pulmonary Auscultation

by Rafael Martínez-Sanz*

Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Universidad de La Laguna, Instituto canario cardiovascular, Tenerife, Spain

*Corresponding author: Rafael Martínez-Sanz, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Universidad de La Laguna, Instituto canario cardiovascular, Tenerife, Spain

Received Date: 10 December 2024

Accepted Date: 16 December 2024

Published Date: 18 December 2024

Citation: Martínez-Sanz R (2024) 54-Year-Old Woman with Intense Dyspnea and Normal Pulmonary Auscultation. J Surg 9: 11211 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011211

Presentation Clinic History

We present a 54-year-old woman with a history of type-2 diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension with left ventricular hypertrophy, depressive syndrome, thyroid nodule with biopsy showing cytological suspicion of category 4 follicular proliferation (Bethesda system), monoclonal gammopathy, vaginal prolapse, hepatic steatosis, simple bilateral renal and hepatic cysts, and diverticulosis of the left colon. A week before going to the cardiologist presents severe dyspnea, but no paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, chest pain or syncope. She recognizes palpitations in the last year. No fever or cough. Neither do other respiratory symptoms (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chest X-ray study, no evidence of the cause of dyspnea.

Physical Examination Findings

Moderate obesity but large breasts, no palpable precordial thrill, no organomegaly, large nodule in the right thyroid lobe. Cardiac auscultation shows a grade IV/VI holosystolic murmur in the aortic focus, not irradiated to the neck or axillae, followed by a slight proto-mesodiastolic murmur. Normal lung and neurological system exam.

Diagnostic Studies

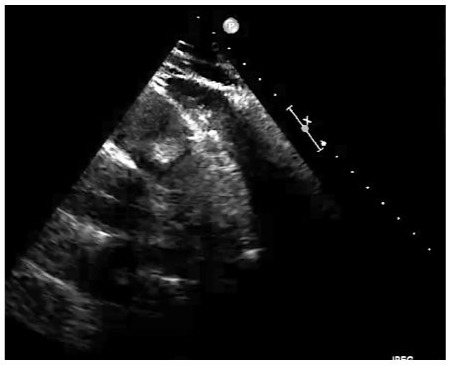

Hemogram, blood chemistry, urine studies, arterial blood gases and coagulation studies were normal. ECG: sinus rhythm, ventricular hypertrophy, incomplete right bundle branch block. RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) negative. Hemocultures (3) of peripheral blood, negative. Echocardiogram: echodense image in the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), interpreted as a thrombus; normal ventricular function. Pelvic ultrasound: increased echogenicity in liver due to possible steatosis, simple cystic formations of 5-12 mm in liver and 25 mm in both kidneys. Abdominal-CT, with findings similar to echoes, ruling out abdominal tumours, with evidence of diverticulitis of the left colon (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE) showing the Right Ventricular Outflow Tract (RVOT), the trunk of the pulmonary artery and the pulmonary valve with an obstructive tumour.

What is the Possible Diagnosis?

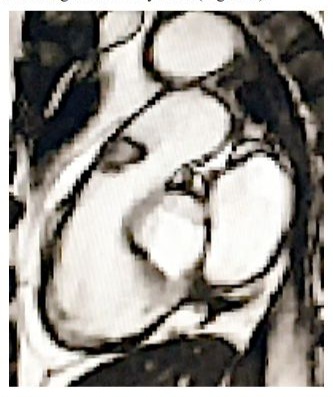

With an initial diagnosis of a mass in the right ventricular outflow tract (possible thrombus), the following are performed: Ecotranseophageal, where an echodense mass of 2.5 cm is better appreciated, rounded and with clear limits, with an anchoring in the anterior face of RVOT and that protrudes in each systole to the trunk of the pulmonary artery, regressing in the diastole to the RVOT, with negligible valve regurgitation (possible diagnosis: myxoma in RVOT). CT-angiography shows a hypodense mass in RVOT, adhered to its wall and protruding through the pulmonary valve, with normal trunk, pulmonary arterial branches and parenchyma, and no debris suggesting pulmonary embolisms (a very probable myxoma diagnosis). MRI shows a 20 mm pedunculated mass in RVOT, a slight increase in the signal in T1 and a slight decrease in T2, with moderate prograsive uptake of with gallodinium contrast, for which the radiologist gives us these three diagnoses in decreasing order of suspicion: cardiac papillary fibroelastoma, slow flow hemangioma and myxoma (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) MRI T1 with contrast, showing the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), the trunk of the pulmonary artery and the pulmonary valve with an obstructive tumour.

Histopathological Diagnosis

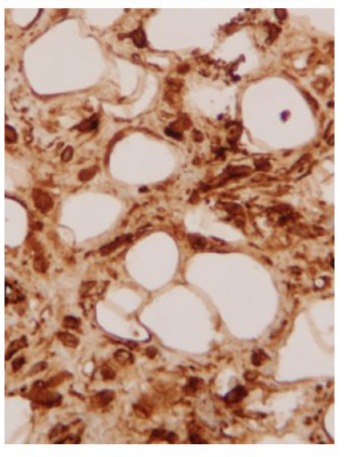

The pathologic specimen was described as well-defined lipomatous formation that stretches its endocardial covering. Tumour area of mature monovacuolar adipocytes with good capsular delimitation of the endocardial strip. Area of spindle-cells and adipocytes, without atypia, and a weft of coarse ropelike bands of collagen fibers. The immunohistochemical study shows immunoreactivity especially in areas for CD-34, positivity for CD-34. Negative for vascular and endocardial endothelial material CD-31. What is the diagnosis? Spindle-cell lipomatous benign tumour of pulmonary valve.

Clinical Course: This patient teaches us that sudden intensedyspnea, with normal pulmonary exploration and with an intense murmur in foci of the cardiac base, not irradiated to the neck or axilla, rules out aortic valve pathology, which is more frequent. We must not forget that any presumably atypical cardiological symptom, with an unusual evolution, accompanied by an unexpected examination or a change in posture, should make us think about ruling out a cardiac tumour.

Diagnosis: The Gold Standard for diagnosis in these cases is echocardiography. CT and MRI brought us closer to the possible etiology, definitively ruling out pulmonary pathology, and allows us to establish a strategy for intervention. Our hospital lacks PET, so the abdominal-pelvic ultrasound and CT ruled out other tumours. Although the tumour in the case presented is rare, his case illustrates how to proceed in other more common valvular tumours.

Post Surgical Evolution: She had a postoperative complicationfree clinical evolution with echocardigraphic control showing good biventricular function, absence of obstruction and minimal pulmonary valve regurgitation. Valve reconstruction in our case avoids complications related to prosthetic valves, such as thrombosis, endocarditis, paravalvular leak or the need for anticoagulation.

Pearls

Cardiac tumours are rare, most are metastatic, but if they are primitive, they are usually benign, with valve tumours being very rare. Atypical cardiological symptom, with an unusual evolution, accompanied by an unexpected examination or a change in posture, should make us think about ruling out a cardiac tumour. The Gold Standard for diagnosis is echocardiography. The surgical results are good and the possibility of recurrence is also very low. We can say that we have a pulmonary valve spindle-cell lipoma which one occluded the RVOT: The rarest cause of the most frequent symptom, dyspnea, resolved by leaflets bicuspidization.

Brief Review of Cardiac Tumours, Specially in Rvot and Lipomatous Heart Tumours

Background: In the heart, cardiac lipomas are rare benign encapsulated tumours made up of mature adipocytes [1-3]. Their cardiac valve location is exceptional, even more so in the pulmonary valve [1,4,5]. We will focus on two important aspects: Valvular heart tumours and lipomas. We will review the symptoms of heart tumours, their diagnosis and treatment. We propose a classification of cardiac lipomas based on their histology and their location. We make a brief review of cardiac tumours, over all valve tumours and cardiac lipomas.

Heart Tumours: They are very rare. Most of them are metastatic [6,7] (up to 95%) [8,9]. We must exclude this adverse possibility in any case of cardiac tumour diagnosis [10,11].

Primary Cardiac Tumours: They are rare [10,12] and most of them are benign [13,14]. However, although histologically the tumour may be benign, its clinical behavior may be malignant and cause death [15,16]. Pheochromocytoma is a type of catecholamine -producing paraganglioma neuralcrest-derived neuroendocrine cell tumour from the chromaffin cells of the sympathetic nervous system [13]. Around 80% are benign and

60% are located in the roof of the left atrium [13]. They are rare entities with an autopsy frequency ranging between 0.001% and 0.3% [17]. Barreiro and colleagues [17] data from 73 patients with a histopathological diagnosis of a primary cardiac tumour in a 32-year retrospective analysis from a Spanish tertiary surgical center. Tissue samples were obtained either at surgery or from necropsy. Benign tumours were 84.9% of cases. The average age was 61 years and tumours were twice as frequent among women [17]. The most common diagnosis was myxoma (93.5%). Less common may be fibroelastomas and lipomas in adults [17,18].

Children’s and young people primary cardiac tumours. Most of the cardiac tumours in children are benign [12]. Mainly are rhabdomyomas [12]. To a much lesser extent, they are described fibromas [12,19], teratomas [12], haemangiomas [12], lipoblastomas [20] and valve hamartomas [21]. Some children with rhabdomyomas had spontaneous tumour regression without intervention [12]. Primary cardiac valve tumours (PCVT) affect all four valves, with approximately equal frequency [22]. China’s Fu Wai Hospital [23] find, in a 19-year retrospective series, at PCVT accounted for 2.65% of all primary cardiac tumours. It was roughly one in 4,000 cardiac operations [23]. From the Wang series [24] of 211 patients with primary cardiac tumours in a 30-year period, only 8 (3.8%) were PCVT: Myxomas 3 cases, fibroelastomas 2 cases, one rhabdomyoma, one lipoma (on pulmonary valve) and one malignant sarcoma. The most common histological type in the Edward’s PCVT series, 22 of 56 cases was papillary fibroelastoma and followed by, but with great difference, myxoma [5], fibroma [4], sarcoma [2], hamartoma [1], hemangioma [1], histiocytoma [1], undifferentiated1. They found no lipomas. Heart valvular myxomas, is a rare disease, affected all four valves, mainly on the mitral valve [25]. We have described one implanted in the tricuspid septal leaflet, the size of a pear, which presented a giant abdominal myxoid cyst four months after hospital discharge [26].

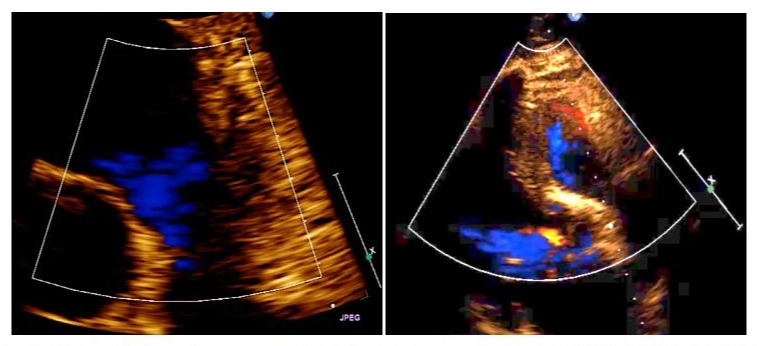

Figure 4: (a) Hospital pre-discharge transthoracic ultrasound showing absence of tumour or obstruction in the right ventricular outflow tract. (b) Hospital pre-discharge transesophageal echocardiography showing minimal pulmonary valve insufficiency.

Cardiac Papillary Fibroelastoma (CPF), is the most common tumour of the heart valves (73.2%) [22,27] and accounts for 7.9 % of benign primary cardiac tumours [28]. Affecting all four valves [29], mainly the left side valves (aortic and mitral valves) [24]. Being aortic valve leaflet location about half of them [28] and the pulmonary valve is the less frequent [30,31]. Many authors have reported individual cases or little series of CPF [32,33]. Bossert and colleagues [34] describe a case of CPF of the aortic valve with temporary occlusion of the left coronary ostium. CPF series is growing due to the fact that echocardiographic studies are more frequent [35,36]. Its etiology appears to be cytomegalovirusinduced chronic endocarditis [37]. “CPFs are generally small and single, occur most often on valvular surfaces, and may be mobile, resulting in embolization” [28,38]. Darvishian and Farmer [39] reported the findings of two cases with a stroke, operated on, and a reviewed of another 77 cases. Aortic CPF is a rare cause of stroke, but every physician should think about it as an option and seek to rule it out with an echocardiography [40]. Bussani and Silvestri [41] describe sudden death in a woman with fibroelastoma in the aortic valve that chronically occludes the right coronary ostium. Some of these cases are described as autopsy findings as a cause of sudden death [42,43]. Sometimes in asymptomatic patients the diagnosis of tricuspid CPF is established in routine exploratory cardiology procedures [44,45], as it may be an unusual cause of intermittent dyspnea [46].

Cardiac hibernomas. Are very rare benign tumours [47]. They usually remain asymptomatic, but they can cause embolisation, pericardial effusion and tamponade, arrhythmia, or blood flow obstruction [48]. Macroscopically, it is a yellowish, soft, smooth mass, with well-defined edges, and without invasion of neighboring structures. Histopathology shows cells with lipid vacuoles and granules with eosinophilic cytoplasm. The F-2-Deoxy-2-fluoroD-glucose (FDG) -positron emission tomography (PET), detects and quantifies functional and metabolic abnormalities of soft tissue masses such as cells with greater avidity or greater glucose metabolism (like tumour cells). However, a high radiotracer uptake by hibernomas has been documented in FDG-PET / CT [48]. The lesion may be isointense with respect to subcutaneous fat in T1-weighted sequences, thus simulating a lipoma; but it is not completely suppressed in fat suppression sequences, unlike lipomas, in which it is suppressed [48]. Primary pulmonary valve tumours (PPVT). Metastasis to the heart is not infrequent but that on valvular tissue is rare, overall, on pulmonary valve [7]. Although infrequent [49,50], the most common PPVT in pulmonary valve is the CPF [27,51]. Primary tumours of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT). Tumours are very rare in this location [52], most of them are rhabdomyomas in babies and myxomas in adults [53,54]. They can produce symptoms due to obstruction in the outlet of the right ventricle, failure of this, or pulmonary embolism (Figure 4).Cardiac lipomas and difuse lipomas. Cardiac lipomas are not common and are usually intramural or epicardial in location1. The second Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) tumour fascicle have lipomas in 8.4% of primary cardiac tumours [55]. In the third fascicle of AFIP, only two among 242 (0.83%) benign cardiac tumours were benign lipomas. In some case they can produce damages in electric conduction system or arrithmyas, as well as interfere on coronary flow (angina) or pump function [1]. Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum (LHAS) was first described by Prior [56] and it is very rare [57] and even less frequent in the interventricular septum [58,59]. It can be the cause of sudden death [60]. Cardiac lipomas can originate either from endocardium [8,61] (approximately 50%), epicardium (25%) [62], or from the myocardium (25%) [63] and may be located more frequently in left ventricle [64] or right atrium [65,66]. Although rarest, they are also described in the right ventricle [58,67]. In some cases, lipomas have been described as multiple in the atria [68]. In other cases, lipomas have been reported as invasive [69]. Cardiac valve lipomas. Cardiac lipomas that sit on its valves are rare [70]. Most of the cardiac valve lipomas have occurred on tricuspid [71,72]or mitral valves (fibrolipoma [73], sclerosed lipoma [74], fatty infiltration [75]). Only a few cases are on aortic or pulmonary valves [5,76]. Matsushita’s series [77] describe seven lipomas in the mitral valve, three in the tricuspid, two in the aortic valve and one in the pulmonary. Roberts and colleagues [78] review the six preceding cases of mitral lipomas described. Some valve lipomas may have been included in series of hamartomas [21,72], fibrolipomas [19,73]or sclerosed lipomas [74], due to present a mixed fat and fibrous tissue composición [16]. Pulmonary valve lipomas. Pulmonary valve lipoma is extremely rare [24]. And they can cause either mechanical obstruction or valve regurgitation. Both can cause severe right ventricular failure. Pederzolli and colleagues [5] report a case of a pulmonary valve lipoma presenting as syncope in a 28-year-old woman.

Spindle-cell lipomas. They are a relatively infrequent variant of benign lipomatous soft tissue tumour [79]with good delimitation and encapsulation [80,81]. It is composed of a variable number of typical spindle-cells together with mature adipocytes in a weft of coarse ropelike bands of collagen fibers [80,81]. The appearance of these tumours ranges from those with thin spindlecell tracts that simulate a common lipoma (as is our case), to those with a net predominance of spindle-cells, which give the tumour a fibrous appearance [80]. Possibly some of the tumours previously described as cardiac fibrolipomas correspond to this lipomatous variant [79,80]. Its diagnosis is established when in the immunohistochemical study there is positivity to the immunostaining in spindle-cells for the CD-34 antigen (endothelial marker and hematopoietic progenitors) and negativity for myogenic markers (to exclude myolipomas), as well as the endothelial marker CD-31 for exclude angiolipomas [79,82]. We know a case of spindle-cell lipoma in heart valves [83]. It was a 64-year-old woman with angina and this type of lipoma in the aortic valve. After removing the tumour, the aortic valve had to be replaced [83]. In this case, Rathore and colleagues [83] insist on the discussion on the importance of staining with CD-34, although his paper does not show any CD-34 picture (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Microphotograph (Å~400) of a well-defined lipomatous tumour of mature monovacuolar adipocytes with area of spindle cells and adipocytes, without atypia, and rope-like bands of collagen fibres, where the immunohistochemical study shows immunoreactivity especially in spindle-cell areas positivity for CD-34.

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnosis of Cardiac Tumours

Symptoms are usually due to embolization of part of the tumour or cloths that can grow over the tumour (stroke). They can also be due to failure of valve closure, obstruction through a valve, compression or displacement of the coronary arteries, alterations over the cardiac electrical system, or occupation of one or more of the cardiac chambers [9,10]. Sometimes they are derived from a constitutional syndrome [41]. From this we can expect symptoms as dyspnea, angina, arrhythmias, or syncope from congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolization, and heart rhythm disturbances [9,10]. We must not forget that it may be an independent and unusual cause of stroke, and the outcomes change after resection of the tumour [84]. Constitutional symptoms like fever, weight loss

or fatigue, and immune manifestations of myalgia, weakness, and arthralgia, may accompany the above symptoms [9,10]. Infection occurs less frequently [41]. The main diagnostic system to confirm the suspicion of an intracardiac tumour is echocardiography [85,86]. Confirmation or pre-surgical nuances, in order to establish an operative strategy, can be carried out with MRI [87,88], CT [89], and to rule out that it is metastatic or a primitive malignant tumour we have PET [90,91].

Discussion

The incidence of adipose cardiac tumours, within its rarity [1], offers differences, according to the concept expressed about them by different authors [1,92]. We make a proposal for the classification of cardiac lipomas based firstly on their histopathology and secondly on their cardiac topographic location (Table 1). The frequency of cardiac lipomas is between 0.3 and 8.4% among cardiac tumours [1,55], because some consider LHAS as a variant of lipoma [70,86]. LHAS has different characteristics with lipomas, as well as heart lipoma of interventricular septum [93], such as its infiltrating appearance and being devoid of capsules [70,86]. In contrast, valvular lipomas have been considered as malformative processes of the lipomatous hamartoma (aortic [21] or tricuspid [72,94]), fibrolipomas [19,73] or sclerosed lipomas [74] that have separated from lipomas [1]. Due to their pathological characteristics, lipomas are distinguishable from hibernomas or tumours of brown fat [47,48], angiolipomas [95], myolipomas [96] and also, due to their incidence in pediatric ages, from lipoblastomas [20]. Clinicopathologically, liposarcomatype cardiac malignant neoplasms are well defined [1]. Cardiac lipomas are solitary in almost 95% of cases [3,86]. Regarding its location in the heart, subendocardial (48.7%), subepicardial (32.5%), myocardial (10.7%), rarely valvular (4.4) [86]. Twelve rare valvular lipomas are reviewed in this 2021 series of systemic review of cardiac lipoma [86]: 6 in mitral, 3 in tricuspid, 2 in aortic, and only one in pulmonary. We could say that any cardiac symptom could be caused by a cardiac tumour, although these symptoms often manifest themselves in an atypical way, for example dyspnea or angina in certain positions and not in others [9,10]. Echocardiography, including transeophageal, is the main tool to confirm the diagnosis [85]. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, MRI and CT will allow us to establish surgical strategies [89]. As the most frequent tumours in the heart are metastatic [6,7], we must rule out this condition to be sure that it is a primitive cardiac tumour [10,11]. Those hospitals that have a PET scan [9,10]can also rule out the malignancy of a primitive tumour in most cases [48]. In many cases, symptoms are usually due to embolization of part of the tumour or cloths that can grow over the tumour. They can also be due to failure of valve closure, obstruction through a valve, compression or displacement of the coronary arteries, alterations over the cardiac electrical system, or occupation of one or more of the cardiac chambers. Sometimes they are derived from a constitutional syndrome. From this we can expect symptoms as dyspnea, angina, arrhythmias or syncope from congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolization, and heart rhythm disturbances. We must not forget that it may be an independent and unusual cause of stroke, and the outcomes change after resection of the tumour. Constitutional symptoms like fever, weight loss or fatigue, and immune manifestations of myalgia, weakness and arthralgia, may accompany the above symptoms. Infection occurs less frequently.

|

Adipose Cardiac Tumourations Classification proposal. |

|

A. Based on basically histopathological criteria: |

|

-Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum (LHAS) |

|

-Lipoma |

|

* Common or conventional |

|

* Fibrolipoma (sclerosed lipoma) |

|

* Myolipoma |

|

* Angiolipoma |

|

* Spindle cell lipoma |

|

-Hibernoma |

|

-Lipoblastoma |

|

-Liposarcomas |

|

B. Based on criteria for cardiac topographic location: |

|

- Interatrial septum |

|

- Interventricular septum |

|

- Subendocardium |

|

- Subepicardium |

|

- Myocardyum |

|

- Atrioventricular node |

|

- Valvular: |

|

* Atrio-ventricular: mitral and tricuspid |

|

* Ventriculo-arterial: aortic and pulmonary |

Table 1: Cardiac adipose tumours. Classification proposal.

Early diagnosis and intervention are key to preserving the normal function of the involved valve and to prevent potential critical events [12,24]. Valve reconstruction in our case avoids complications related to prosthetic valves, such as thrombosis, endocarditis, paravalvular leak or the need for anticoagulation. Surgical resection generally results in a complete cure, which provides an excellent long-term prognosis for these patients [24,97]. The minimally invasive approach for escision of benign cardiac tumours is a low-risk procedure and perhaps superior to standard full sternotomy, but this is controversial because they are based on only a few retrospective studies [80,82]. Sometimes the defect caused by resection of the lipoma can be reconstructed without the need for foreign materials [97]. In case of lipoma valvular implant, if possible, the best option is to keep the valve [73,99] to avoid complications inherent to a prosthesis [100]. A macroscopically very similar tumour located in the leaflets of the pulmonary valve, such as the CPF, was resolved by Grus and colleagues [101] preserving the anatomical structure by valvesparing surgery.

References

- Veinot JP (2008) Cardiac tumors of adipocytes and cystic tumor of the atrioventricular node Semin Diagn Pathol 25: 29-38.

- Ismail I, Al-Khafaji K, Mutyala M (2015) Cardiac lipoma. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 19; 5: 28449.

- Bois MC, Bois JP, Anavekar NS, Oliveira AM, Maleszewski J (2014) Benign lipomatous masses of the heart: a comprehensive series of 47 cases with cytogenetic evaluation Hum Pathol 45:1859-1865.

- Grande AM, Minzioni G, Pederzolli C, Rinaldi M, Pederzolli N et al (1998) Cardiac lipomas. Description of 3 cases J Cardiovasc Surg 39: 813-815.

- Pederzolli C, Terrini A, Ricci A, Motta A, Martinelli L et al (2002) Pulmonary valve lipoma presenting as syncope Ann Tharac Surg 73: 1305-1306.

- Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahales GJ (2007) Malignant tumours of the heart: a review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 19:748-756.

- Goldberg D, Blankstein R, Padera RF (2013)Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation 128: 1790-1794.

- Singh S, Singh M, Kovacs D, Benatar D, Khosla S et al (2015) A rare case of a intracardiac lipoma Internat J Surg Case Reports 9: 105-108.

- Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, et al (2005) Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management Lancet Oncol 6:219228.

- Bruce CJ (2011) Cardiac tumors: diagnosis and management. Heart 97: 151-160.

- Paraskevaidis IA, Michalakeas CA, Papadopoulos CH, AnastasiouNana M (2011) Cardiac tumors ISRN Oncol 2011: 208929.

- Stiller B, Hetzer R, Meyer R (2001) Primary cardiac tumours: when is surgery necessary? Eur J Cardiothor Surg 20: 1002-1006.

- Nassar MI, de la Llana Ducrós R, Bonis E, Garrido P, Alarcó A, et al (2006) Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma involving the left atrium: An infrequent pathologic occurrence J Thor Cardiovasc Surg 132: 14601461.

- 14. Tyebally S, Chen D, Bhattacharyya S Cardiac (2020)Tumors: JACCCardioOncologyState-of-the-Art ReviewJACC:CardioOncology 2:293-311.

- 15. Sajeev CG, Kalathingathodika S, Nair A (2014) Malignant arrhythmia with benign tumour: fibrolipoma of the left ventricle. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 22: 151-154.

- Benvenuti LA, Mansur AJ, Lopes DO, Campos RV (1996) Primary lipomatous tumors of the cardiac valves South Med J 89: 1018-1020.

- Barreiro M, Renilla A, Jimenez JM (2013) Primary cardiac tumors: 32 years of experience from a Spanish tertiary surgical center. Cardiovasc Pathol 22: 424-427.

- Piazza N, Chughtai T, Toledano K, Sampalis J, Liao C (2004) Primary cardiac tumours: eighteen years of surgical experience on 21 patients. Can J Cardiol 20: 1443-1448.

- Barberger-Gateau P, Paquet M, Desaulniers D, Chenard J (1978) Fibrolipoma of the mitral valve in a child. Clinical and echocardiographic features Circulation 58: 955-958.

- Dishop MK, O’Connor WN, Abraham S, Cottrill CM (2001) Primary cardiac lipoblastoma. Pediatr Rev Pathol 4: 276-280.

- Wada T, Miyamoto S, Anai H, Zaizen H, Hadama T (2005) Aortic valve lipomatous hamartoma in a young woman. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg; 53: 577-579.

- Edwards FH, Hale D, Cohen A, Thompson L, Pezzella AT, et al (1991) Primary cardiac valve tumors. Ann Thorac Surg 52: 1127-1131.

- Huang Z, Sun L, Ming D, Ruan Y, Wang H (2003) Primary Cardiac Valve Tumors: Early and Late Results of Surgical Treatment in 10 Patients Ann Thorac Surg 76: 1609-1613.

- 24. Wang Y, Wang X, Xiao Y (2016) Surgical treatment of primary cardiac valve tumor: early and late results in eight patients J Cardiothorac Surg ; 11: 31.

- Grubb KJ, Jevremovic V, Chedrawy EG (2018) Mitral valve myxoma presenting with transient ischemic attack: a case report and review of the literature J Med Case Rep 12: 363.

- de la Llana Ducros R, Wilhelmi M, Alvarez J, Rey Naya J, Gutierrez JR, et al (1987) Recurrence potentiality of cardiac myxomas. Case report with tricuspid implantation site of the tumor. Rev Esp Cardiol 40: 210-212

- Park MY, Shin JS, Park HR, Lim HE, Ahn JC, et al (2007) Papillary fibroelastoma of the pulmonary valve. Heart Vessels 22: 284-286.

- Sun JP, Asher CR, Yang XS, Cheng GG, Scalia GM, et al (2001) Clinical and Echocardiographic Characteristics of Papillary Fibroelastomas: A Retrospective and Prospective Study in 162 Patients. Circulation; 103: 2687-2693.

- 29. Truscelli G, Gaudio C (2014) Papillary fibroelastoma of the pulmonary valve-a systematic review: advantages of live/ real time three-dimensional transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Echocardiography; 31: 795-796.

- Costa MJ, Makaryus AN, Rosman DR (2006) A rare case of a cardiac papillary fibroelastoma of the pulmonary valve diagnosed by echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 22: 199-203.

- Hakin FA, Aryal MR, Pandit A (2014) Papillary fibroelastoma of the pulmonary valve--a systematic review. Echocardiography 31: 234-240.

- 32. Guo DC, Yang YH, LiuY (2019) Incidental finding of an asymptomatic pulmonary valve papillary fibroelastoma: A case report. J Clin Ultrasound 47: 568-571.

- 33. DaccarettM, Burke P, Saba S (2006) Incidental finding of a large pulmonary valve fibroelastoma: a case report. Eur J Echocardiogr 7: 253-256.

- Bossert T, Diegeler A, Spyrantis N, Mohr FW (2000) Papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve with temporary occlusion of the coronary ostium. J Heart Valve Dis 9:842-843.

- Howard RA, Aldea GS, Shapira OM, Kasznica JM, Davidoff R (1999) Papillary fibroelastoma: increasing recognition of a surgical disease. Ann Thorac Surg 68: 1881-1885.

- Gowda RM, Khan IA, Nair CK, Mehta NJ, Vasavada BC, et al (2003) Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: A comprehensive analysis of 725 cases. Am Heart J 146: 404-410.

- Grandmougin D, Fayad G, Moukassa D (2000) Cardiac valve papillary fibroelastomas: clinical, histological and immunohistochemical studies and a physiopathogenic hypothesis J Heart Valve Dis 9: 832-841.

- Generali T, Tessitore G, Mushtaq S, Alamanni F (2013) Pulmonary valve papillary fibroelastoma: management of an unusual, tricky pathology. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 16: 88-90.

- Darvishian F, Farmer P (2001) Papillary Fibroelastoma of the Heart: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Clinical Lab Science 31: 291-296.

- 40. Kumar V, Soni P, Hashmi A, Moskovits M (2016) Aortic valve fibroelastoma: a rare cause of stroke. BMJ CaseReports 2016: (bcr2016217631).

- Bussani R, Silvestri F (1999) Sudden death in a woman with fibroelastoma on the aortic valve chronically occluding the right coronary ostium. Circulation 100: 2204.

- Prahlow JA, Barnard JJ (1998) Sudden death due to obstruction of coronary artery ostium by aortic valve papillary fibroelastoma. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 19: 162-165.

- Takada A, Saito K, Ro A, Tokudome S, Murai T (2000) Papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve: a sudden death case of coronary embolism with myocardial infarction. Forensic Sci Int 113: 209-214.

- Strecker T, Scheuermann S, Nooh E, Weyand M, Agaimy A (2014) Incidental papillary fibroelastoma of the tricuspid valve. J Cardiothorac Surg 9: 123.

- Cardy C, Riddle N, Dunning J, Chen A (2019) Giant tricuspid valve fibroelastoma incidentally diagnosed during routine stress testing. JACC: Case Reports 1: 564-568

- Georghiou GP, Erez E, Vidne BA, Aravot D (2003) Tricuspid valve papillary fibroelastoma: an unusual cause of intermittent dyspnea. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 23: 429-431.

- 47. Strecker T, Reimann A, Voigt JV, Papadopoulos T,Weyand M (2006 ) A very rare cardiac hibernoma in the right atrium: a case report. Heart Surg Forum 9: E623-625.

- Mata-Caballero R, Saavedra-Falero J, López-Pais J, Molina-Blázquez L, Alberca-Vela MT, et al (2017) Cardiac hibernoma in the right atrium and around superior cava vein. A case report. Cir Cardiov. 5: 314-316.

- 49. Ibrahim M, Masters RG, Hynes M, Veinot JP, Davies A (2006) Papillary fibroelastoma of the pulmonary valve. Canadian J Cardiol 22: 509510.

- Hannecart A, Ndjekembo-Shango D, Vallot F, Simonet O, De Kock M (2017) Primitive Tumour of the Pulmonary Valve: Discussion of the Differential Diagnosis.Case Rep Crit Care 2017: 6263578.

- Okada K, Sueda T, Orihashi K, Watari M, Matsuura Y (2001) Cardiacpapillary fibroelastoma on the pulmonary valve: A rare cardiac tumor Ann Thorac Surg 71: 1677-1679.

- Gopal AS, Stathopoulos JA, Arora N, Banerjee S, Messineo F (2001) Differential diagnosis of intracavitary tumors obstructing the right ventricular outflow tract. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 14: 937-940.

- Jayaprakash K, Madhavan S, Kumary S, Anish PG, George R (2015) Benign neoplasms in the right ventricular outflow tract Proc (Babyl Univ Med Cent) 28: 67-68.

- Gribaa R, Slim M, Kortas C (2014) Right ventricular myxoma obstructing the right ventricular outflow tract: a case report J Med Case Reports 8:435.

- Burke A, Tavora FR, Maleszewski JJ, Frazier AA (2015) Benign tumors of fatty tissue. In Tumors of the heart and great vessels (AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Series 4 Bethesda (MD),American Registry of Pathology ed, pp. 189-99.

- Prior JT (1964) Lipomatous hypertrophy of cardiac interatrial septum: a lesion resembling hibermoma, lipoblastomatosis and infiltrating lipoma Arch Pathol 78: 11-15.

- Bielicki G, Lukaszewski M, Kosiorowska K, Jakubaszko J, Nowicki R (2018) Lipomatous hypertrophy of the atrial septum - a benign heart anomaly causing unexpected surgical problems: a case report BMC Cardiovasc Disord 18: 152.

- Fang L, He L, Chen Y, Xie M, Wang J (2016) Infiltrating lipoma of the right ventricle involving the interventricular septum and tricuspid valve: Report of a rare case and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 95: e2561.

- Li D, Wang W, Zhu Z, Wang Y, Xu R, et al (2015) Cardiac lipoma in the interventricular septum: a case report. J Cardiothoracic Surg 10:69.

- Hejna P, Janík M (2014) Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum: a possibly neglected cause of sudden cardiac death. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 10:119-121.

- Behnam R, Williams G, Gerlis L, Walker D, Scott O (1983) Lipoma of the mitral valve and papillary muscle. Am J Cardiol 51: 1459-1460.

- Wu S, Teng P, Zhou Y, Ni Y (2015) A rare case report of giant epicardial lipoma compressing the right atrium with septal enhancement. J Cardiothoracic Surg 10: 150.

- Wang H, Hu J, Sun X, Wang P, Du Z (2015) An asymptomatic right atrial intramyocardial lipoma: a management dilemma. World J Surg Onc 13: 20

- Akram K, Hill C, Neelagaru N, Parker M (2007) A left ventricular lipoma presenting as heart failure in a septuagenarian: a first case report. Int J Cardiol 114: 386-387.

- Wang X, Yu X, Ren W, Li D (2019) A case report: a giant cardiac atypical lipoma associated with pericardium and right atrium. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 19:247.

- Sankar NM, Thiruchelvam T, Thirunavukkaarasu K, Pang K, Hanna WM (1998) Symptomatic lipoma in the right atrial free wall. A case report. Tex Heart Inst J 25: 152-154.

- 67. Schrepfer S, Deuse T, Detter C (2003) Successful resection of a symptomatic right ventricular lipoma. Ann Thorac Surg 76: 1305-1307.

- Smith MA (2007) Multiple synchronous atrial lipomas. Cardiovasc Pathol 16: 187-188.

- D’Souza J, Shah R, Abbass A, Burt JR, Goud A, et al. (2017) Invasive Cardiac Lipoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 17: 28.

- Burke A, Tavora FR, Maleszewski JJ, Frazier AA (2015) Classification and incidence of cardiac tumors. In Tumors of the heart and great vessels (AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Series 4, vol. 22) 2015.

- Jiang X, Liu J, Gu T (2021) Successful resection of a posterior tricuspid leaflet lipoma and reconstruction of tricuspid valve. Ann Thorac Surg 2021: 00181-188.

- Crotty TB, Edwards WD, Oh JK, Rodeheffer RJ (1991) Lipomatous hamartoma of the tricuspid valve: echocardiographic-pathology correlations. Clin Cardiol 14: 262-266.

- Caralps JM, Marti V, Ferres P, Ruira X, Subirana MT (1998) Mitral valve repair after excision of a fibrolipoma. Ann Thorac Surg 66: 18081809.

- Harth M, Ruemmele P, Knuechel-Clarke R, Elsner D, Riegger G (2003) Sclerosed lipoma of the mitral valve. J Heart Valve Dis 12: 722-725.

- Anderson DR, Gray MR (1988) Mitral incompetence associated with lipoma infiltrating the mitral valve. Br Heart J 60: 169-171.

- Surdacki A, Kapelak B, Brzozowska-Czarnek A, et al. (2007) Lipoma of the aortic valve in a patient with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 115: e36-38.

- Matsushita T, Huynh AT, Sing T, et al. (2007) Aortic valve lipoma. Ann Thorac Surg 83: 2220-2222.

- Roberts WC, Grayburn PA, Hamman BL (2017) Lipoma of the mitral valve. Am J Cardiol 119: 1121-1123.

- Goldblum J, Weiss S, Folpe AL, Benign Lipomatous Tumors (2019) In Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors, 7th Edition. John Goldblum, Sharon Weiss, Andrew L. Folpe ed. Philadelphia (PA). Elsevier 2019: 476-519.

- Miettinem M (2010) Lipoma variants and conditions simulating lipomatous tumors. In Modern soft tissue pathology: Tumors and non-neoplastic conditions. Markku Miettinen ed. Cambridge (UK). Cambridge University Press 2010: 343-393.

- The WHO Classification of tumours Editorial Board. Spindell cell lipoma and pleomorphic lipoma. In Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours. WHO Classification of tumours, 5th ed; vol 3. Edited by The WHO Classification of tumours Editorial Board. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer 2020: 29-30.

- Shah OA, Badran A, Kaarne M, Velissaris T. (2019) Right atrial and SVC infiltrating mass-the entity of infiltrating lipoma. J Cardiothor Surg 14: 210.

- Rathore KS, Stuklis R, Allin J, Edwards J (2010) Spindle cell lipoma of the aortic valve: a rare cardiac finding. Cardiovasc Pathol 19: e9-e11.

- Elbardissi AW, Dearani JA, Daly RC, et al. (2009) Embolic potential of cardiac tumors and outcome after resection: a case-control study. Stroke 40: 156-162.

- Meng Q, Lai H, Lima J, Tong W, Qian Y, et al. (2002) Echocardiographic and pathologic characteristics of primary cardiac tumors: a study of 149 cases. Int J Cardiol 84: 69-75.

- Shu S, Wang J, Zheng C (2021) From pathogenesis to treatment, a systemic review of cardiac lipoma. J Cardiothorac Surg 16: 1.

- Constantine G, Shan K, Flamm SD, Sivananthan MU (2004) Role of MRI in clinical cardiology. Lancet 363: 2162-2171.

- Fieno DS, Saouaf R, Thomson LE, Abidov A, Friedman JD, et al. (2006) Cardiovascular magnetic resonance of primary tumors of the heart: a review. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 8: 839-853.

- van Beek EJR, Stolpen AH, Khanna G, Thompson BH (2007) CT and MRI of pericardial and cardiac neoplastic disease. Cancer Imaging 7: 19-26.

- Auger D, Pressacco J, Marcotte F, Tremblay A, Dore A, et al. (2011) Cardiac masses: an integrative approach using echocardiography and other imaging modalities. Heart 97: 1101-1109.

- Motwani M, Kidambi A, Herzog BA, Uddin A, Greenwood JP, et al. (2013) MR imaging of cardiac tumors and masses: a review of methods and clinical applications. Radiology 268: 26-43.

- Kempson RL, Flecher CDH, Evans HL, Hendrickson MR, et al. (2001) Tumors of the soft tissue, 3th. Bethesda (MD). AFIP 2001: 187-208.

- Alves MR, Gamboa C (2020) Cardiac lipoma of the interventricular septum. Eur J Case Rep Inter Med 7: 001685.

- Janik M, Kucerova S, Ublova M, Hejna P (2013) Giant Lambl’s excrescence: a rare incidental finding at autopsy. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 9: 585-587.

- Kiaer HW (1984) Myocardial angiolipoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Inmunol Scandin A 92: 291-292.

- Petrov A, Silaschi M, Treede H, Wilbring M (2018) Primary Cardiac Myolipoma - Initial Description and Further Follow-up. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 66: S1-S110.

- Koshida Y, Watanabe G, Tomita S, Iino K, Noda Y (2012) Right atrial lipomatous hypertrophy resection and reconstruction using autologus pericardium. Surg Today 42: 1104-1106.

- Pineda AM, Santana O, Cortes-Bergoderi M, Lamelas J (2013) Is a minimally invasive approach for resection of benign cardiac masses superior to standard full sternotomy? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 16: 875-879.

- Sauchelli-Faas G, Barragán-Acea A, Hugo Álvarez-Argüelles et al. (2023) Pulmonary valve spindle-cell lipoma: A case report. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports 11: 1-5.

- Dollar AL, Wallace RB, Kent AM, et al. (1989) Mitral valve replacement for mitral lipoma associated with severe obesity. Am J Cardiol 64: 1405-1407.

- 101. Grus T, Kuchynka P, Palecek T, Hadravsky L, Urbanec T, et al. (2020) Papillary fibroelastoma on pulmonary valve – Valve-sparing surgery of a cardiac tumor in a rare location. Cardiovasc Pathol 46: 107195.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.